Subjects

Grades

The reliability of measuring instruments determines how well a measurement obtained by one device gives an exact result that can be reproduced at another time by another person who will obtain a similar result.

Theoretically, two people carrying out the same laboratory work under similar conditions should obtain identical results. However, when it comes to taking data in the laboratory, two types of error can occur.

Random errors: These are errors that occur when a large number of measurements are taken. These errors can be caused by the person carrying out the manipulations or by a change in the measurement to be taken (as, for example, if we were trying to measure wind velocity).

Systematic errors: These are errors relating to the measuring instrument that can be corrected by adjusting the instrument appropriately. This type of error will always affect the results in the same way. The smaller the systematic error, the more exact the results.

The main aim of this concept sheet is to assess the effect of the measuring instrument on the quality of the results. The reliability of measuring instruments is assessed on the basis of four parameters.

| Precision |

A measuring instrument is precise if the difference between two graduations is small. |

| Consistency |

A measuring instrument is consistent if it is able to give the same result for the same measurement under similar conditions. |

| Sensitivity |

A measuring instrument is sensitive if the variations between different measurements are large. |

| Accuracy |

A measuring instrument is accurate when it allows measurements to be taken with very little error. |

A measuring instrument is precise if the difference between two graduations is small.

Absolute uncertainty can be used to determine which instrument is more precise. To determine the absolute uncertainty of a non-electronic or non-digital instrument, take half the smallest scale, whereas the absolute uncertainty of a digital or electronic instrument corresponds to the smallest scale displayed.

A precise instrument will have the smallest absolute uncertainty.

To measure a volume of |\small \text {20.0 ml}| of water, it is preferable to use a graduated cylinder of |\small \text {25.0 ml}|, which has an uncertainty of |\small \pm \text {0.3 ml}|, rather than a graduated cylinder of |\small \text {50.0 ml}|, which has an uncertainty of |\small \pm \text {0.4 ml}|, because the first instrument is more precise than the second.

Generally speaking, it is preferable to use relative uncertainty as the definitive measure of precision. The smaller the relative uncertainty, the greater the precision of the measurement.

The following distances were measured in the laboratory: |\small \left( 100 \pm 2 \right) \: \text {cm}| and |\small \left( 10 \pm 1 \right) \: \text {cm}|. Which of these two measurements is more precise?

For the first measurement:

||\begin{align} \text {I.R.} = \frac{\text {Absolute uncertainty}}{\text {Measured value}}\times \text {100} \quad \Rightarrow \quad \text {I.R.} &=

\frac {2 \: \text {cm}}{100 \: \text {cm}}\times \text {100} \\ \\

&= 2 \: \% \end{align}||

For the second measure:

||\begin{align} \text {I.R.} = \frac{\text {Absolute uncertainty}}{\text {Measured value}}\times \text {100} \quad \Rightarrow \quad \text {I.R.} &=

\frac {1 \: \text {cm}}{10 \: \text {cm}}\times \text {100} \\ \\

&= 10 \: \% \end{align}||The first measurement is therefore more precise, although its absolute uncertainty is greater.

A measuring instrument is consistent if it is able to give the same result for the same measurement under similar conditions.

Consistency is determined by the dispersion (or range) of the results. If several measurements are made on the same object, we can expect the results to be similar. On the other hand, if there are significant variations between these measurements, the consistency of the measurements may be questioned.

Consistency can be studied in terms of two components.

A student in a physics laboratory finds that the time taken for a ball to fall from a height of one metre is |\small \left( 0.45 \pm 0.01 \right) \: \text {s}|. He repeated his measurements a few minutes later, and obtained measurements of |\small \left( 0.45 \pm 0.01 \right) \: \text {s}| et |\small \left( 0.46 \pm 0.01 \right) \: \text {s}|. He may mention that repeatability is good, as the measurements are similar in all three tests.

A student uses an electronic balance and obtains a mass of |\small \left( 39.56 \pm 0.01 \right) \: \text {g}|. A few minutes later, his team-mate returned to weigh the same object on the same scales in the same place. He obtained a measurement of |\small \left( 40.41 \pm 0.01 \right) \: \text {g}|. It can therefore be said that the instrument's reproducibility is very poor.

A measuring instrument is sensitive if the variations between different measurements are large.

A device is very sensitive if a small variation in a parameter causes a large change in the measurement indicated by the measuring instrument.

An instrument with graduations is sensitive if the graduations are widely spaced, since it is easier to take a measurement with this type of instrument.

Digital or electronic instruments generally have a higher sensitivity than other types of instrument, such as analogue instruments.

A measuring instrument is accurate when it allows measurements to be taken with very little error.

A trueness error is an overall error that encompasses all the causes of error for each of the measurement results taken individually.

The accuracy of a measurement can be calculated by determining the average of the measurements taken experimentally, and then calculating the difference between this average and the theoretical value (or expected value). A very small difference means that the measurements taken in the laboratory are accurate.

A first student determines that the gravitational acceleration obtained by the fall of a ball is |\small 9.74 \: \text {m/s}^2| after carrying out five tests. Another student in his group carried out the same experiment and calculated the gravitational acceleration to be |\small 9.89 \: \text {m/s}^2|. The first student obtained a more accurate value, because the deviation from the expected value, |\small 9.81 \: \text {m/s}^2|, is smaller for her results (a deviation of |\small 0.07 \: \text {m/s}^2|) than the deviation from the expected value for the second pupil (|\small 0.08\: \text {m/s}^2|).

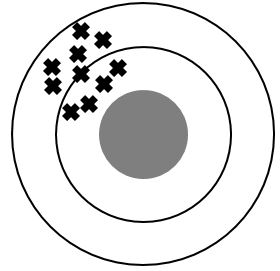

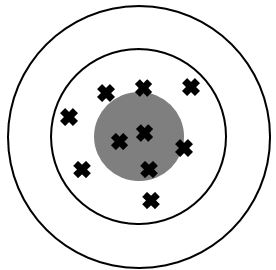

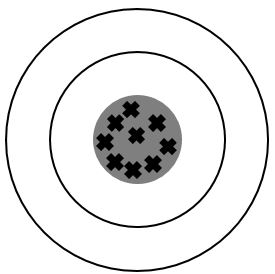

The following images represent situations in which the consistency and accuracy of measurements are assessed. The images can be imagined as coming from someone throwing darts at a target.

An accurate result is close to the expected value.

A consistent result has a small dispersion (the results are close to each other).

|

|

|

Inconsistent results

Inaccurate results Presence of random and systematic errors |

Consistent results

Inaccurate results Presence of systematic errors |

|

|

|

Inconsistent results

Accurate results Presence of random errors |

Consistent results

Accurate results Minor errors |