Subjects

Grades

The concepts covered in this factsheet go beyond those seen in secondary school. It is intended as a supplement for those who are curious to find out more.

An artefact is an object that was produced and used by people to carry out one of their daily activities: hunting, fishing, eating, tool-making, farming, etc. Artefacts have an important heritage value and allow us to study and understand objects linked to the past.

Artefacts can be made of a variety of materials: stone, metal, ceramic, bone, wood, etc. Studying artefacts gives us a better understanding of how people lived in the past.

Finding artefacts is an important contribution to history, but they still need to be analysed to extract as much information as possible. There are two methods for studying artefacts: conventional observational analysis and laboratory analysis.

The observational analysis is carried out in three stages.

The aim of laboratory analysis of materials is to discover aspects that are not visible during observational analysis or where such analysis proves insufficient. Laboratory analysis can identify where the artefact was made, the manufacturing techniques used and its precise use. There are various methods of laboratory study (microscope, chemical analysis). As with observational analysis, the laboratory results must be compared with the results obtained and noted in the various directories of similar objects.

This method of interpretation aims to note all the characteristics of the artefact, place the object in its context and find its meaning.

The method can be summed up in five main questions:

What is it? What object is it? What are its properties (materials and construction)? What tools were needed to make it? Is it a reproduction? Why was this object designed? How was it used?

Where was this artefact produced? Where was it used?

And when? There are three questions we need to ask in order to establish the time path of an artefact. When was it produced? When was it used? When was it found?

Who produced it? Who produced the object? Who was it used for? Who kept it? Who found it?

Why is this? What is the significance of the artefact?

Once all these questions have been answered, it is time to reflect on the significance of the artefact: to link the answers found to related knowledge about a wider range of artefacts, and to link these answers to knowledge about the historical and social context of manufacture and use. We can attempt to define what value was attributed to the artefact by its maker and its user.

Finally, why should the artefact be preserved? What significance does it have for local, regional, national or international history?

Observation can help historians and archaeologists to date found objects. However, more precise methods exist to avoid errors. The relative method involves estimating the age of an object in relation to the layers of soil. If the soil is made up of different strata, the deeper strata will contain objects from a more distant past. On the other hand, the layers closer to the surface will contain more recent objects.

This makes it possible to date an artefact according to the stratum in which it was found and according to other objects found in the same soil stratum. This method is useful during excavation. However, if historians wish to establish a more precise date, there are two more rigorous methods for dating objects: radiocarbon dating and potassium-argon dating.

Radiocarbon dating, or Carbon-14 dating, is useful for dating organic materials such as wood, charcoal and bone. However, this method can only calculate the date of death of these materials. Potassium-argon dating enables volcanic rocks to be dated accurately. It can only date the age of the ore, not the age of the object.

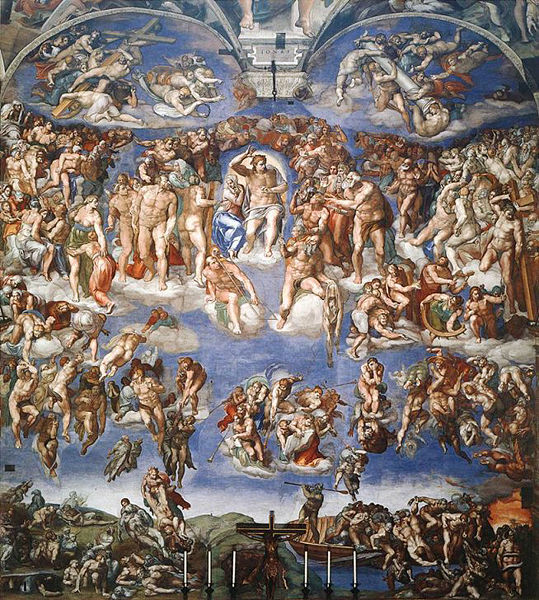

Using a precise technique, a fresco is a mural painting that has been created on a plaster that is still fresh. This precise method enables the colour pigments to be fixed permanently. This is why many frescoes are still clearly visible today.

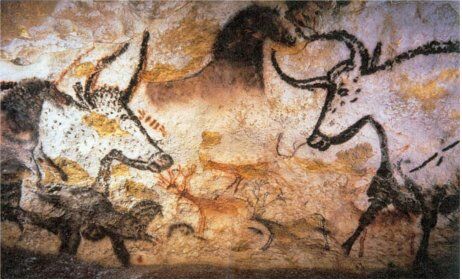

This is a very old technique, the first examples of which come from cave paintings, including those in the Lascaux caves. It is estimated that these paintings date from between 18,000 and 15,000 BC.

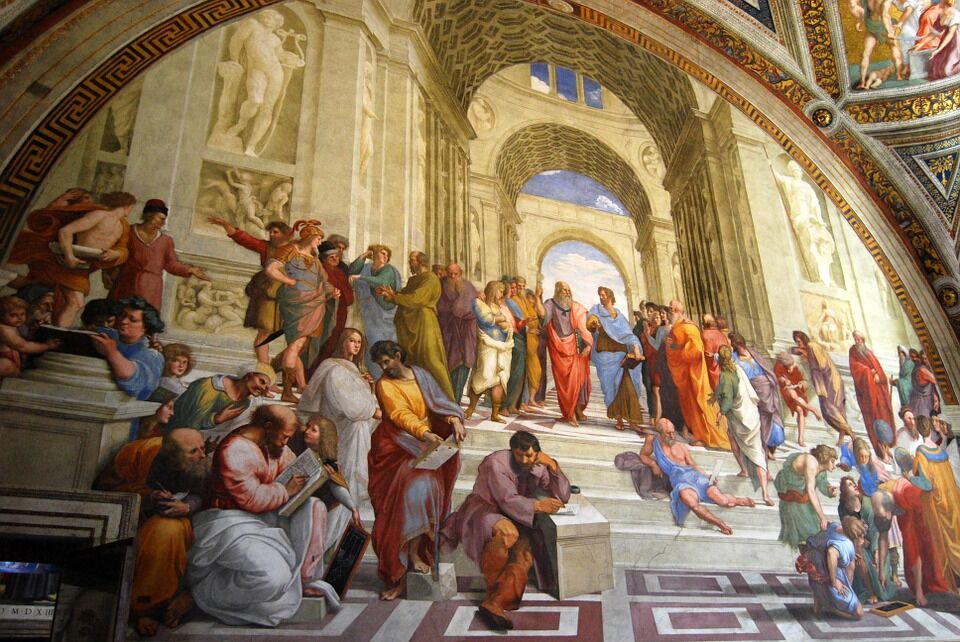

The first real frescoes, produced using the technique and the use of lime, are estimated to date back to 1800 BC. Many examples of frescoes from different periods can still be admired today, including the hypogeums of Egypt, the tombs of Erutria and Pompeii. In Europe, the heyday of frescoes came during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, mainly in Italy. The best-known examples were created by Renaissance painters such as Michelangelo.

There are also several frescoes in France, including at the Château de Fontainebleau and the Château de Versailles, as well as in several Romanesque churches.

Studying the fresco serves several purposes: