Subjects

Grades

To access the other concept sheets in the Heritage Cities unit, check out the See Also section.

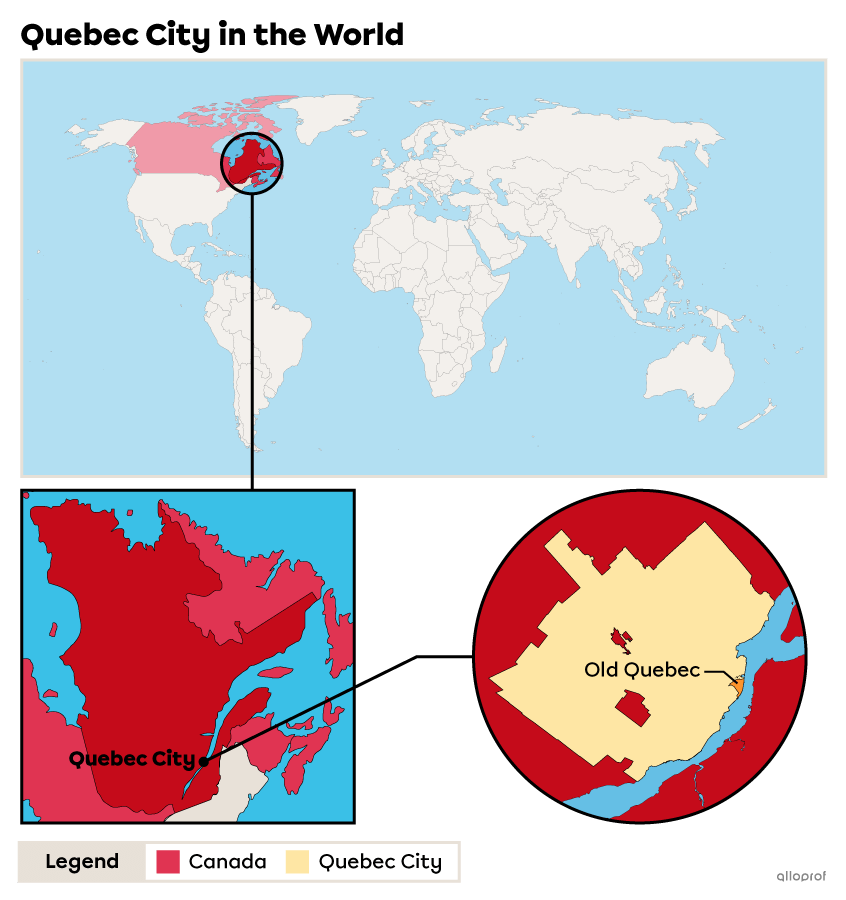

Quebec City is located on the north shore of the St. Lawrence River, in the province of Quebec, Canada.

The city covers an area of 453.26 km2[1]. The heritage site occupies approximately 1.35 km2 of the city’s territory[2], or barely 0.3 % of the territory of the entire city.

Quebec City is the oldest French-speaking city in North America. Founded in 1608 by Samuel de Champlain on Indigenous land, it has been a capital since the period of New France.

The city’s heritage site is located on either side of Cap Diamant, a cliff that divides the city into the Upper Town and the Lower Town. There are fortifications in the Upper Town (in particular the ramparts). Within these is located the area known as intra-muros (which means “within the walls”). This area consists of historical, administrative and religious buildings. The heritage site also extends to part of the Lower Town, between the foot of the cliff and the St. Lawrence River. In the past, this was the site of port and commercial activities. Both of these areas make up Old Quebec, Quebec City’s heritage site.

Quebec City’s Heritage Site

A cliff is a rocky escarpment with a steep slope.

The historic district of Old Quebec has been on UNESCO’s World Heritage List since 1985. UNESCO recognized the site as a world heritage element because it is an exceptional example of a fortified colonial city.

The fortifications are more than 4 km in length[4]. One portion dates back to the French regime (of New France), and the rest was built during British rule. They surround the heritage site located in the Upper Town. They can still be seen today and even visited on foot.

Place Royale is located close to the St. Lawrence River in Quebec City’s Lower Town. It is surrounded by many buildings, including Notre-Dame-des-Victoires church, which dates back to 1688, making it the oldest stone church in North America.

Below Place Royale and the Notre-Dame-des-Victoires church are remnants (ruins) of Samuel de Champlain’s second house. The site has been used for many activities since, including a public market until the end of the 19th century.

Founded when the religious community arrived in North America in 1639, the Ursuline monastery has seen generations of nuns and students pass through its doors over centuries. The Ursulines were dedicated to girls’ education. The monastery includes several buildings, and now houses a museum and a school.

The Ursuline monastery’s courtyard and entrance.

The Augustine monastery includes several buildings. The oldest ones date back to 1695. Between 2013 and 2015, major work, including archeological research, was conducted, leading to an addition to house a museum collection as well as the transformation of part of the monastery into a hotel. Since the Augustine community had cared for the sick for centuries, they ensured that the care and well-being of others continues to be a part of the new mission.

The Augustine monastery’s chapel

Founded in 1663, the Québec Seminary’s first mission was to train priests in the colony of New France. The building also housed the first French-language university: the Université Laval. Today, it is still used and houses the university’s school of architecture.

The oldest part of the house dates back to 1690, making it one of the oldest houses in the province of Quebec. It is one of the few to have conserved its original architecture. There have nevertheless been many modifications over time, including major additions in the 19th century. It is named after François Jacquet dit Langevin, its first owner.

This district is named after its main street, Petit-Champlain Street. For decades, this district was home to workers and artisans. Today, it is a lively area that attracts many tourists, with restaurants, shops and entertainment venues.

Petit-Champlain Street

The Citadel of Quebec was a British fort built between 1820 and 1850. It includes two buildings dating back to the time of New France. The Citadel is part of the fortifications of Quebec City and includes one of the residences of the Governor General of Canada. It is an active military base to this day, housing the headquarters of the Royal 22nd Regiment.

The star shape of the exterior walls leaves no blind spots, allowing for an effective defence of the Citadel.

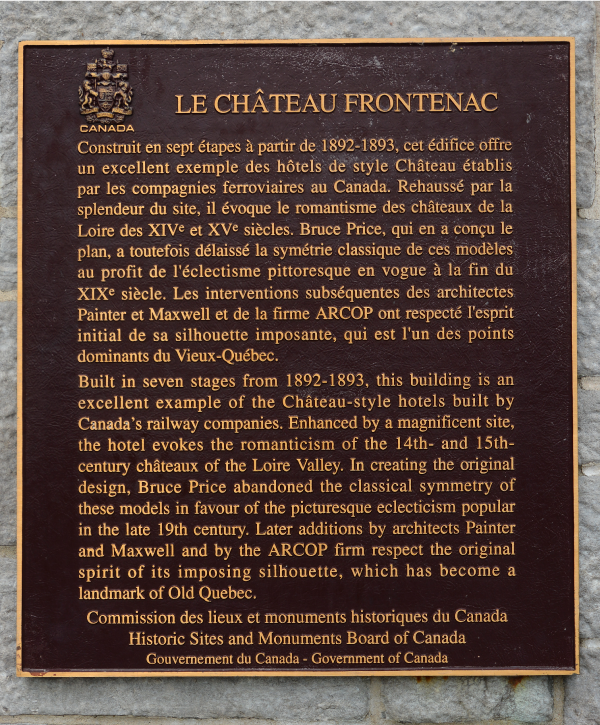

Even though it has “château” in its name, Château Frontenac was never a king’s residence. The Canadian Pacific railway company had it built as a hotel in 1893 for tourists visiting Quebec City. It is believed to be the most photographed hotel in the world.

Dufferin Terrace is a long boardwalk at the foot of Château Frontenac. It was inaugurated in 1838 and at the time was called the Durham Terrace. In 1878, when it was expanded, it was given its current name. It is visited during summer and winter, by both residents and tourists.

Built between 1929 and 1931, the Price Building is the only skyscraper in the historic district of Old Quebec. It was named after the company that ordered its construction, the Price Brothers, which, at the time, was the leading newsprint producer in Canada. Today, it houses offices as well as the official residence of Quebec’s Premier.

The construction of the Price Building prompted the introduction of a law to limit the height of buildings.

Old Quebec is divided into two levels: the Lower City and the Upper Town because these neighbourhoods are separated by a cliff. Stairways and a funicular have been built to make it easier to get between the two.

The streets in the old city are narrow and measures have been put in place to make it easier to use them.

Some of the streets are one way.

Parking is prohibited on certain streets.

Emergency services and the city's public works services must use vehicles adapted to the streets.

Public transportation buses are smaller

In the planning and development of Old Quebec, various measures have been taken to respect its heritage character.

Buildings cannot surpass a certain height

Specific materials must be used for the renovation or reconstruction of buildings

The district’s vegetation must be respected. If a tree is cut down, it must be replaced

Commercial signs on shops must respect the district’s architecture

Certain buildings are classified as historic monuments and must preserve their historic style, both inside and outside

In the early 1960s, the Quebec government recognized the historic value of Old Quebec and developed a plan to protect and promote it. At the end of the 1960s, work was done to restore the Lower City, in particular Place Royale.

Funicular in Old Quebec

The funicular connects Petit-Champlain Street and Dufferin Terrace.

Place-Royale

Place-Royale is part of the old city that was restored in the style of the French regime.

Saint-Jean Street

Shops must respect the district’s heritage character.

Old Quebec receives millions of visitors each year. For instance, in 2019, more than 3.6 million people visited the old city[8]. The area of Old Quebec is 1.35 km2, which means that a lot of planning and development is required to receive all these visitors[2].

Amenities Specific to Tourists

Tourist information centres

Tourist Information Office in Old Quebec

Information plaques and panels

Château Ramezay Information Plaque

Restaurants and souvenir shops

Petit-Champlain Street

There are many shops and restaurants on this street.

Hotels and inns

Auberge du Trésor in Old Quebec

Signage for finding the intra-muros district

Signs Indicating the Main Tourist Sites in Old Quebec

Ferry terminal

Ferry Terminal in the Old Port

Bus tours that stop at various tourist attractions

Tourist Bus in Old Quebec

Place-Royale square

Place-Royale

Opening of public toilets near tourist attractions.

Panel Indicating Public Toilets on Petit-Champlain Street

Panels indicating the public toilets in Old Quebec all have the same appearance so that tourists can easily identify them. In the photograph above, the panel is on the left wall.

Tourism puts significant pressure on the Old Quebec neighbourhood.

To accommodate tourists, many houses have been transformed into inns or hotels, and apartments are rented to tourists during their stay.

The businesses in the districts respond more to the needs of tourists (restaurants, souvenir shops, art galleries, etc.) than those of residents (grocery stores, pharmacies, dental clinics, etc.).

There is less housing available for residents. This shortage means that housing prices are increasing. Without housing or without affordable housing, residents have to find somewhere else to live.

Residents must leave the neighbourhood in order to do essential shopping, such as groceries.

The number of people living in Quebec City’s heritage site is decreasing from year to year. Between 1996 and 2016, the number dropped by 9%[12] to 4689 residents in Old Quebec in 2016[13].

The fact that residents are leaving the district could have a negative impact on tourism. Tourists want to see the authenticity of the city, with the people who live there. In other words, it is the residents that make the city lively.

A rowhouse on Saint-Denis Street in Old Quebec.

Certain measures have been put in place to keep residents in Old Quebec:

facilitate access to affordable housing

transform unoccupied buildings into housing

ensure that there is a hospital or health care clinic nearby

help local businesses, such as a pharmacy or grocery store, open up in the district

better distribute major events (like the Carnival of Quebec) across the city to prevent large crowds from gathering in the heritage site

provide access to public transportation

The Comité des citoyens du Vieux-Québec, a committee created in 1975 by a group of citizens to defend the interests of the residents of Old Quebec, keeps informed about decisions affecting the historic district in order to promote the needs of residents and, if necessary, propose more adapted solutions.

The tourism industry in Old Quebec is constantly expanding. During the 2019 tourist season, 236 715 cruise ship passengers on 150 ships visited the city[10]. Quebec City’s port hopes to double this number by 2025.

In addition to visitors arriving by ship, there are also those who come by bus. Old Quebec receives more than 30 000 buses and coaches each year[11]. Each bus carries dozens of travellers.

Many tourists also travel to the city in their own cars.

The presence of all of these different means of transportation is the source of a major air, visual and sound pollution problem in Old Quebec.

There are many consequences related to the cruise ships that stop in Quebec City’s port.

The ships are a source of significant greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs) because their engines run 24 hours a day

The ships release their wastewater (from the toilets, washing machines, dishwashers) into the St. Lawrence River, which has harmful consequences for the river’s marine ecosystems

The ships often use heavy fuels that emit large quantities of sulfur oxides, a type of air pollution that is very harmful to health

The ships also create a lot of sound pollution. Some residents living close to the port have moved away due to the noise from the engines, especially at night

The ships sometimes emit unpleasant odours, such as diesel fumes

The 30 000 buses that circulate in Old Quebec each year generate significant pollution.

They are responsible for much of the greenhouse gas emissions in the district

It is not unusual for them to park on Saint-Louis Street and leave their motors running

The concentration of buses in front of Château Frontenac and on the narrow streets of Old Quebec creates visual pollution, but also sound pollution caused by their engines.

Several solutions have already been put in place or will be in the next few years to reduce the pollution problem related to the tourism industry in Old Quebec.

A few solutions have already been proposed for the pollution created by the cruise ships.

In 2015, the Canadian government established a standard on sulfur emissions, known as the ECA standard. It sets the limit at 0.1%, which is much stricter than standards elsewhere in the world (3.5%)[10]. Cruise ships must change their fuel or have an air filtration system when they enter Canadian waters.

Transport Canada’s goal is to make the new environmental measures regarding the release of wastewater mandatory by 2023. These new regulations limit what ships can release into the ocean. They are much stricter than the international standards of the International Maritime Organization.

One solution to the pollution caused by buses would be to establish incentive parking outside Old Quebec and prohibit buses from entering the district. Another proposed solution is to transform Old Quebec into a pedestrian zone or to prohibit access to vehicles.

To access the rest of the unit, you can consult the following concept sheets.