Subjects

Grades

To access the other concept sheets in the Indigenous Territory unit, check out the See Also section.

The Inuit are an Indigenous people who have lived in the Arctic region of Canada for close to 1000 years. In 2021, the Inuit population of Canada was 70 545, of whom 44% lived in Nunavut[3]. The term Inuk refers to a member of the Inuit people.

There are eight ethnic Inuit groups in Canada:

the Labrador Inuit (Labradormiut)

the Ungava Inuit

the Baffin Island Inuit

the Iglulik Inuit (Igluligmiut)

the Caribou Inuit (Kivallirmiut)

the Netsilik Inuit (Netsilingmiut)

the Copper Inuit (Inuinnait)

the Western Arctic Inuit

The Inuit language is divided into five main dialects. Those used by the Nunavut Inuit are Inuktitut and Inuinnaqtun.

Since they live in isolated regions, contact between the Inuit and Europeans occurred later than with other Indigenous nations. This meant that the Inuit were able to preserve their traditions and their culture remained unchanged until the mid-20th century.

The Inuit were a nomadic people. They travelled using sled technology and dogs, providing a fast and efficient mode of transportation over ice and snow. Their way of life was adapted to the polar climate and the tundra. Nordicity was the basis of their culture. They travelled in small groups and followed herds of animals. In the winter, they hunted seal on the pack ice and in the summer they travelled inland to hunt caribou. They also hunted whales.

The products from their hunt allowed them to be self-sufficient:

the meat served as food for the members of the group

the skins and furs were used to make clothes and tents that protected them from the cold

the bones and ivory served to make tools and sculptures

The Inuit only hunted what they needed.

Nomadic refers to a person or group of people who travel to meet their food needs.

Nordicity refers to all of the characteristics of living conditions in northern regions (cold, snow, isolation).

Self-sufficiency refers to the capacity of an individual, a group or a country to respond to its own needs without external help.

Starting in the mid-19th century, the Inuit began trading with Europeans who were coming to hunt whales or take part in the fur trade. The Inuit gradually left their self-sufficient economy and started hunting and fishing more commercially. The European goods (wools, metal items, firearms) they received trading with Europeans also changed their way of life.

In the 1950s, profound changes came with the forced relocation and settlement of the Inuit. With the goal of assimilation and sedentarization, the Canadian government made it a requirement for the Inuit to live in villages. Additionally, the federal government made school mandatory for their children.

Sedentary refers to a person or group of people who are permanently settled on their territory.

In 1953 and 1955, the Canadian government decided to pressure 19 families, or close to 100 people, to relocate from the Inuit communities of Inukjuak and Mittimatalik. Canada put pressure on these families to settle in the High Arctic, more specifically in Resolute Bay and Craig Harbour, more than 2000 km north. The Canadian government wanted to support its territorial claims to the Arctic region by having people living in the region permanently. The Inuit were not in a position to refuse, even if the relocation separated them from family.

Government agents tried to convince Inuit families to make the move by promising them better living conditions. They said that the new territories had abundant game, and promised that the families could return after two years if they wanted to. When the families arrived on site, they discovered that these claims were untrue. Their adaptation to the new living environment was very difficult because of the extreme cold, isolation, little food and a winter without sunlight for three months.

In Craig Harbour, the Inuit families learned that they would be separated again, since some of them were required to settle in Resolute Bay. Many were very upset by this news, since they had agreed to relocate with the sole goal of being kept together as a family.

Despite the Canadian government’s promise, the Inuit who wanted to return home after two years were not able to do so. They learned that they would have to pay their own travel expenses, which was impossible for many of them because the little money they made through trapping was deposited into an account managed by the government to which they had no access.

After years of demands by the Inuit communities, the Canadian government officially apologized in 2010.

Today, the Inuit are sedentary, living in permanent villages. While they no longer hunt as a means of subsistence, hunting and fishing continue to be a very important activity for the Inuit.

The communities now use new means of transportation, in addition to sledding, to travel over the land including snowmobiles, motor boats and planes.

Ancestral rights refers to the fishing, hunting and trapping rights accorded to one or more Indigenous groups based on their ancestral customs.

The average age of the population of Nunavut is 27 years, which is much younger than the average age in the rest of Canada (41 years)[9]. This means there are many individuals of working age. However, many people are unable to find jobs, resulting in high unemployment rates. There are many reasons for this. For example, few jobs are available and the general level of the population's education is low. This is because access to educational services in remote regions is difficult.

Without employment income, it can be difficult for people to meet their needs since food and other items are very expensive in Nunavut due to the remoteness and isolation of the territory.

One solution to address this lack of employment is to exploit the territory’s natural resources, which would create jobs and improve the population’s quality of life.

Unemployment refers to a period during which a person is without a job, but is able to work and is actively looking for a job.

The unemployment rate refers to the percentage of people who are unemployed in a given population.

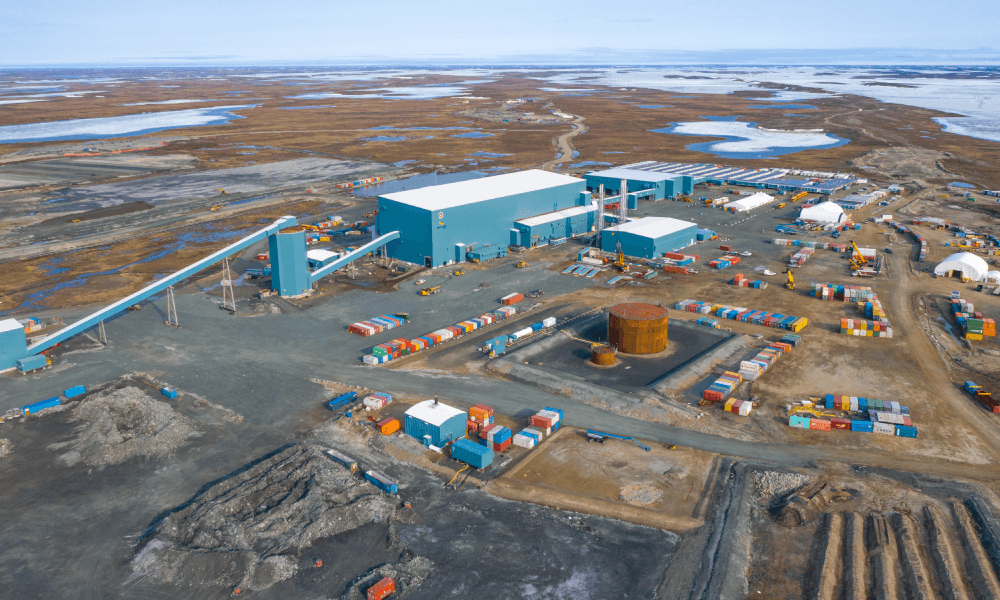

Nunavut has a very promising mining sector. A few mines are already operating on the territory, and many initiatives are underway to open more mines.

Mines require the construction of significant infrastructure to extract, store and transport the resources. This infrastructure profoundly changes the territory and has many negative impacts on the environment. For example, mining waste can release many heavy metals that are toxic for the flora and fauna and can pollute drinking water sources.

Mines also disrupt the Inuit way of life. For example, when a mine opens on a traditional hunting territory, the noise causes game to flee to areas that are often less accessible to hunters. The planning and development of a mine requires a sharing of the territory between the Inuit population’s traditional activities and the mining activities.

One solution is to establish conditions that regulate the development of the mining industry. This could include implementing laws or regulations requiring the companies to minimize their negative impacts on the Inuit’s way of life and on the environment. Restoring the site once the mining activity is complete and asking for financial compensation are two examples of measures that could reduce the negative impacts.

The Meliadine gold mine is located close to the village of Rankin Inlet. This proximity involves many changes, both positive and negative.

The mine has created many job opportunities for the village’s residents. An agreement reached with the company stipulates that it must hire and train staff so that 50% of its employees are Inuit. For each year that the company does not reach this level, it must pay financial compensation to the Kivalliq Inuit Association (which represents the Inuit in the region).

The company has committed to improving its practices by reducing the negative impacts of its operations on traditional activities, such as hunting.

Many people are needed to operate the mine, which puts pressure on the housing sector of the village of Rankin Inlet. Like many other villages in Nunavut, it lacks housing as well as infrastructure for drinking water and wastewater. At present, the village cannot accommodate more people, including workers coming from other communities.

In 2020, the company did not employ enough Inuit to respect its agreement. The members of the community have greater difficulty obtaining certain jobs due to the limited access to post-secondary education in the area.

The mine’s presence makes hunting more difficult because the animals that were once on the territory have moved farther away.

Aerial View of the Installations at the Meliadine Mine

Tourism is another sector that contributes to the economic development of Nunavut. The territory’s big open spaces attract outdoor, hunting and fishing enthusiasts. There are also four national parks on the territory.

Tourism can be a significant source of revenue although income varies depending on the number of visitors. At this time, Nunavut’s tourism sector generates less profit than the mining sector. The main challenge is that Nunavut is an expensive destination, which, in turn, limits the number of tourists. As well, tourist infrastructure is limited. However, the impact of tourism on the environment is generally small, with tourism often promoting the Inuit way of life.

Nunavut is particularly vulnerable to global warming. The Arctic is one of the regions the most affected by climate change.

An increase in temperature of 3 to 7 degrees is predicted by 2030[11]. Between 1948 and 2016, the average temperature in Nunavut increased by 2.7 degrees Celsius, while the average temperature in the rest of Canada increased by 1.7 degrees[12].

This temperature increase is causing an acceleration in the melting of the ice melt (pack ice), the thawing of the permafrost, an increase in sea level and more precipitation.

|

Impacts of Global Warming on the Environment |

Negative Consequences for Communities |

|---|---|

|

Thawing of the Permafrost |

Permafrost is a solid base for structures, but if it thaws, the soil will become soft and could collapse. This could be dangerous for the inhabitants, as well as damage infrastructure, such as roads, bridges, landing strips and houses. |

|

Increase in Sea Level |

This could cause floods as well as the erosion of coastal areas. The villages of Clyde River, Hall Beach and Kugluktuk are particularly at risk. |

|

Shorter and Less Predictable Ice Season |

This affects travel on ice roads. |

|

Gradual Melting of the Pack Ice, Affecting the Seal and Polar Bear Populations |

This affects traditional Inuit activities, such as hunting and fishing. |

|

Increase in Precipitation |

This could cause floods and cause damage to infrastructure. |

Erosion is the deterioration of the soil under the effect of wind, rain or human activity.

Nunavut’s isolation and remoteness present a number of challenges for its inhabitants, such as:

Due to the isolation and remoteness of the communities in Nunavut, food transportation is much more expensive. On average, food costs 2.2 times more in Nunavut than elsewhere in Canada.

Groceries are so expensive that many families in Nunavut are not able to cover all of their expenses. Since many inhabitants live below the poverty line, an increase in the price of groceries has serious consequences for the population.

In 2018, food insecurity affected 57% of the population of Nunavut[13]. With the increase in food prices, rising to 7.4% between 2021 and 2022[14], food insecurity will affect a growing number of families in Nunavut.

There has been a housing crisis (serious shortage of housing) for more than 20 years in Nunavut. The Nuvanut Housing Corporation builds 75 to 100 housing units each year, but that is not enough to meet the needs of the territory’s population. Between 250 and 300 housing units need to be built each year in order to manage housing for the entire population[15].

This is an unrealistic goal for a number of reasons, starting with the significant increase in the price of construction materials, in addition to very high transportation costs. The materials must be transported directly to each community since the communities are not connected to each other by roads. What’s more, the building season is very short, which limits the number of housing units that can be built in a year.

The housing crisis primarily affects the members of the Inuit community, who represent 85% of the population of Nunavut. Many families live in houses that date back more than 50 years, and have had few or no renovations since.

Approximately 56% of Inuit houses are overpopulated, with up to 20 people living in some of them. This leads to other issues in terms of disease, mental health and substance abuse (drugs and alcohol). The suicide rate, for example, is 10 times higher in Nunavut than in the rest of Canada[16].

With isolation and remoteness comes limited access to health services. With no large urban centres on the territory, families in Nunavut must often travel to get specialized medical care.

Some care can be provided at the Qikiqtani General Hospital in Iqaluit, but there are families that have to travel much further for medical specialties that are not available in Nunavut.

Each year, hundreds of children must travel more than 2800 km to the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario (CHEO). In 2019, some 544 children from Nunavut were treated there. The trip can be very challenging for families, who must take two planes and travel more than 12 hours to get to Ottawa. Once there, the different languages and culture can sometimes make the stay difficult. It is not unusual for these families to have to leave their community for several weeks at a time. Even if the cost of the travel and accommodation are paid for, certain families cannot afford to be without income for several weeks. Parents are often separated from their children, since their transportation costs are rarely reimbursed.

To access the rest of the unit, you can consult the following concept sheets.