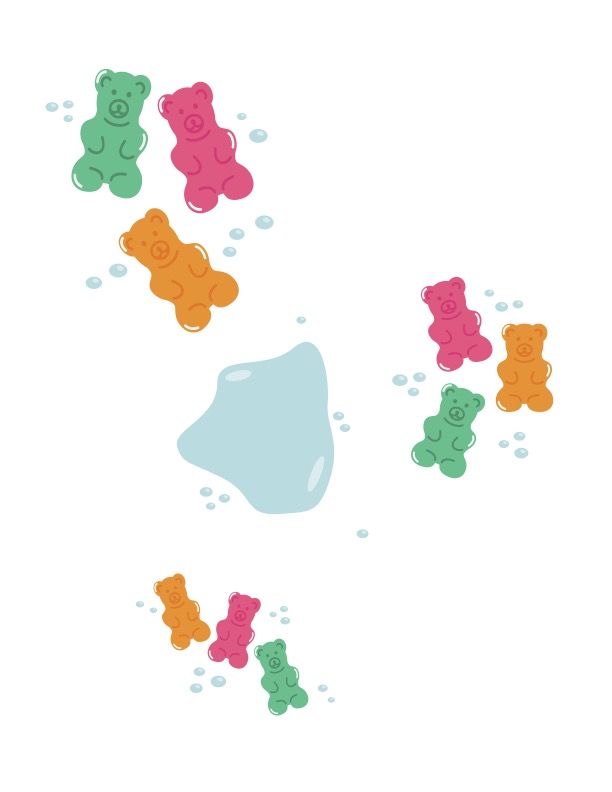

Gummy bears are a delicious treat, but they also make excellent test subjects. In this experiment, students will place gummy bears in sugar water, salt water, and plain tap water, and observe what happens. Some of the gummy bears will shrink, while others will grow. Tip: for a fun twist, you can relate the experiment to the Goldilocks story!

Materials:

-

Gummy bears (at least a dozen per experiment, so you can have four sets of three)

-

Hot water (to be handled by the teacher only) and room temperature water

-

Salt (at least 8 tablespoons per cup of water)

-

Sugar (at least 8 tablespoons per cup of water)

-

A measuring cup with a spout

-

A spoon

-

Three bowls or containers

Instructions:

Add salt to a bowl of hot water and stir with a spoon to dissolve. Keep adding more salt until it no longer dissolves completely and settles at the bottom of the bowl. Repeat this process with the sugar in a second bowl. Finally, fill the third bowl with freshwater (tap water). You now have your three different baths.

Allow the water to cool to room temperature. When the water has cooled, place a few gummy bears in each bowl. Leave a few out of the water so you can compare their size later.

Leave the gummy bears in the water for several hours, ideally overnight. Surprise! Some grow a little (sugar solution), some will grow a lot (freshwater), and some will shrink (salt solution).

Why this experiment works:

This experiment explores osmosis, the movement of water through a barrier (like a gummy candy). Gummy bears contain water molecules. Water molecules naturally move toward areas with higher concentrations of salt or sugar. Because of this, the gummy bears in the experiment will grow or shrink as water moves in or out of them.

In the bowl with tap water, water moves into the gummy bear, and the gummy bear grows. Why? The water moves to equalize the concentrations of dissolved substances in the water. The water outside the gummy bear does not contain any salt or sugar. The interior of the gummy bear contains water and sugar trapped inside the pockets of gelatin. Because the sugar concentration is higher inside the gummy bear, the water moves into the candy.

(Think of it as a sugar cube dissolving in a cup of water. If you let it sit long enough, the water at the top of the cup will be as sweet as the water at the bottom.)

What about the salt water bath? In this case, the water outside the gummy bear is filled with salt. The gummy bear itself contains water and sugar. Salt molecules are much smaller than sugar molecules, so more of them can dissolve in water. This means that the concentration of salt in the water is higher than it is inside the gummy bear. As a result, water moves out of the gummy bear to try and equalize the concentrations, and the gummy bear shrinks.

The gummy bear in the sugar water will grow even though there is sugar in the water and in the candy. This tells us that there must be more sugar inside the gummy bear than there is in the water outside it.

What about other candies?

You might wonder why gummy bears change size while other candies (like mints) just dissolve. Gummy candies, unlike mints, contain gelatin (which does not dissolve in room temperature water) and sugar (which does). At the microscopic level, gelatin contains tiny pockets that can hold liquid. As you can see in this experiment, these pockets can hold a lot of liquid!